Tamara Murphy in conversation with Rae Helms, 2021

Tamara Murphy: Historically, I connect printmaking to the rise of many social movements. It seems to bring power to voiceless communities through low cost/high visibility repetitive imagery. Did your interest in social justice draw you to printmaking or vice versa?

Rae Helms: I started my college career as a political science major; I wanted to be a lawyer. I didn't start creating art until I was almost finished with my political science degree. My frustration from being in the political science field led me to seek other outlets for my passions. I have always been ardent about social issues and engaged in advocacy, but I was angry because I was always talked over and ignored due to my identity and my lack of a PhD. I didn't enjoy the aggressive debates during those classes and the politics that resulted in Trump being elected to office. When I took an introduction to drawing class for a general education requirement, I fell in love with creating and continued to enroll in every art class that I had access to. Being an art major is completely different. The artist has the final say on the artwork's true intentions, meaning, and purpose. I like having my own voice in critiquing social issues, raising awareness against inequalities, and exposing political laws. I have always wanted to challenge institutions and the status quo, this time I am doing so in an art context. I started taking art history classes during this time as well, and in doing so, history has become heavily influential to my practice. Art history is the study of not only history and artwork, but also culture, religion, the differences in class, science, technique, and a window to political upheaval in certain eras. After taking many art history classes, I started comparing art institutions to political institutions and considering the hierarchy of mediums in a museum setting. Historically, fine art is considered oil painting or sculptures made of bronze or marble. Since becoming an artist, I wanted to challenge the concept of what fine art is supposed to be. I began making artwork that focused heavily on what is considered craft: sewing, quilting, and embroidery. I was first introduced to printmaking at Chico State by studying prints in the Janet Turner Printmaking Museum. I learned about the history of printmaking and how the medium has been marginalized as a craft because of the commercial value through creating multiples. Printmaking also has a long history of being a tool for activism and is prevalent in counterculture movements. I fell in love with the art form to convey social change. As a printmaker, I am continuing this long history of blending activism and art, as well as challenging the status quo.

Tamara Murphy: Can you walk me through your creative process? Do you make a lot of preliminary sketches before starting the printmaking process?

Rae Helms: I spend more time researching my concepts and intentions than making work. I keep a notebook with a growing list of ideas. This helps me when I experience artist block. At least 90% of these ideas don't become reality as I have a tough time staying focused on one subject at a time, I enjoy experimenting with the printmaking processes, and working with a wide range of themes. Art history heavily informs my practice. Felix Torrez-Gonzalez and his use of metaphors that brought awareness to the AIDS epidemic was influential to me when I started using symbology for social issues. Learning about Doris Salcedo's work, specifically her Chair installation that represents anonymous refugees who were victims of war, was also significant to my own conceptual thought process, as symbolism became important to my artistic practice. Recently, I have been researching the symbolism of traps and cages; animal traps act as a metaphor for oppressions. My own reflections of my past does lead its way into my work, although subtly. For example, my dad was in the L.A. prison for most of my adolescence, and I think about that physical entrapment a lot.

Additionally, I keep up with current news and newly passed legislation, critique laws that are specifically designed to entrap individuals in our society. My most recent work has focused on the abortion bans placed throughout the US which criminalize females seeking the right to choose. I am horrified by the current attack on Roe v. Wade and immediately thought anti-choice legislation was reminiscent of how animals are captured in the wild. After starting my trap series, I discovered that these enactments are called TRAP (targeted restrictions on abortion providers) laws. These laws are in place to keep marginalization a part of our society because they are designed to affect lower income families that cannot afford to travel when seeking medical treatment. Many laws in the US deliberately cultivate poverty and the rich gain profit from other's misery through the means of lobbying. Moreover, I walk around my area and take photos. For example, after coming up with the concept for my prints Bounty (2021) and Plan B (2021), combining the trap motif with different forms of birth control, I sought out physical rabbit traps. I specifically used this type of trap for the universal symbolism of fertility that rabbits hold. After I have taken photographs, I work digitally to plan composition, layers, and values needed for the final print. Printmakers often plan every step of their process. However, I still enjoy changes or mistakes that occur.

Bounty, 2021, Aquatint/Etching, printed size: 12x17.5’’

Bounty, 2021, Aquatint/Etching, printed size: 12x17.5’’

Tamara Murphy: How important is the medium to your message? Does the ability to print in repetition mean anything for your work?

Rae Helms: At first, creating multiples was the most important aspect to my work. I had the goal to reach the largest audience possible. My first woodcut prints, like Unattended (2020) and Weighed Down (2020), focused on repetition of objects and the creation of multiples. If I am creating a print that is made specifically for a print exchange or making a zine, there's still a focus on multiples to convey a message to as many people as I can reach.

I consider the different processes in printmaking and what each can represent. When I create, I am constantly thinking of symbolism and metaphors through the imagery I use and from the materials I work with; aesthetics isn't my first priority. For example, when I work with aquatints, I consider the fragility of the medium and then view those prints as intimate. My recent aquatint, Bounty, wasn't made to be printed 100 times. Instead, I was focused on the fragility and aggressiveness of the aquatint medium. I think of etching as aggressive because the acid being used to create an image is simultaneously destroying the copper. I also view aquatints as a delicate medium because the final image can be easily ruined because the copper is being crushed each time it is run through the press. The birth control pills and the animal trap being represented in Bounty also focus on this duality of delicacy and robustness. Further, I like the permanence in printmaking. If I was to attempt to “erase” my mistakes, it would take a great amount of work to do so, which is reminiscent of our history and social institutions. The lasting marks on the surface of a plate indicate the lasting damage done by social structures.

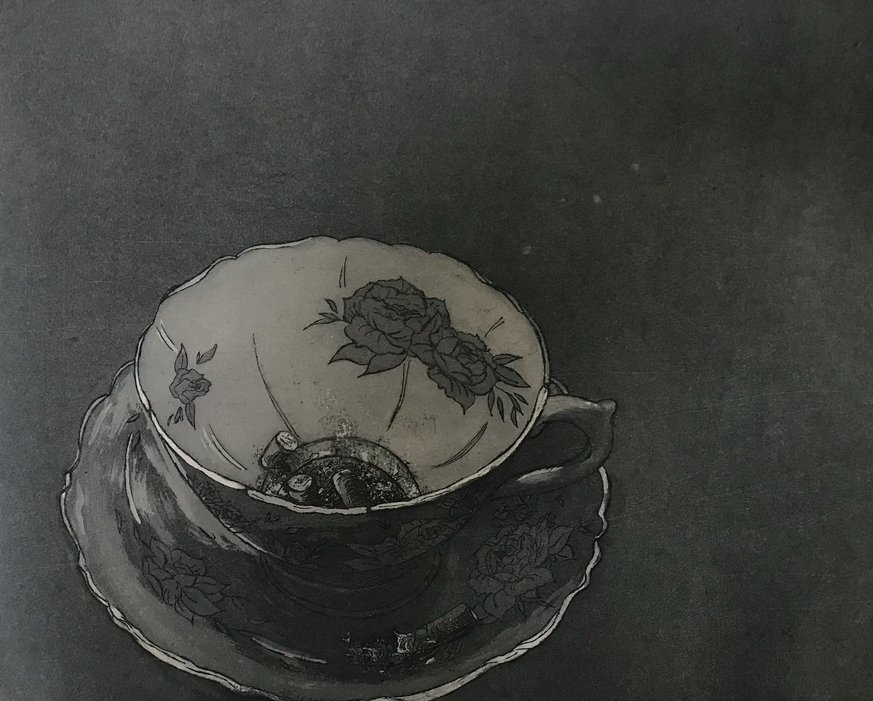

Middle Class, 2021, Aquatint/Etching, printed size: 9x12’’

Middle Class, 2021, Aquatint/Etching, printed size: 9x12’’

Tamara Murphy: You often seem to work in conversation with a specific place and the social inequalities that arise there. How has your relocation to northern California affected your artwork?

Rae Helms: Even though my hometown is only 8 hours away by car, I did experience a culture shock when I first moved to Chico. The most obvious shock was the physical environment. Here, everything is green! There are trees! And absolutely no tumble-weed in sight! Another immediate shock was the lack of diversity in Chico, compared with LA county. Chico is also cheaper to live in, there's more job opportunities, there's an art community and a great amount of community involvement. I wasn't used to these differences therefore I had a hard time adjusting. My artwork initially reflected these differences.

After living here for almost 3 years, I've started to focus on the similarities. There are problems in Chico, despite the overall appearance of a thriving and perfect college town. There's a huge homeless crisis, violence on campus, and a class division between neighborhoods. These problems are not unique to Chico, they are seen in almost every town in the US. I became more interested in symbology and considering universal metaphors through everyday objects. My etching Middle Class (2021) combines a teacup with cigarette ashes. As a child, I viewed my grandma chain smoking and then filling her antique porcelain teacups with cigarette butts. One of my hobbies is going to yard sales and antique stores to look for references to use and I commonly find similar teacups at these places that are reminiscent of my childhood experience. You would be surprised to know how many teacups in antique shops smell like tobacco and ash! I seek out symbols like this that connect to a shared experience. I made Middle Class as a metaphor for middle class families struggling. Just like a fragile and delicate teacup, those average families look healthy and well on the outside, but in reality so many are struggling.

Tamara Murphy: Speaking of your print Middle Class, porcelain is usually considered a high-class material. How does this imagery represent class division?

Rae Helms: I took an art history class called Modern History of Interiors, Furnishings, and Architecture before making Middle Class. We studied the turn of the century in western Europe and the Arts and Crafts movement which included the rise of porcelain factories when the demand for porcelain increased. They were extremely toxic environments to work in, due to the porcelain dust. This history made me think about the exploitation of the working class that still occurs today. Today, porcelain isn't uncommon in a family setting; although porcelain can be viewed as a high-class possession, I view it as a symbol of struggling families.

Tamara Murphy: Is your art usually in response to your own experiences, or are you often inspired by the people around you?

Rae Helms: I think that question is more so about my ideology of the artist and the artist's reasons to create. I believe everyone is influenced by their environment, background, and growth in some respects. I had a rough childhood and adolescence by growing up in poverty. This made me view power imbalances early on in my life; therefore, my artwork is about power imbalances within society, objects, and ourselves. If I'd had a completely different upbringing, I don't think my artwork would look the same. I don't immediately think of my artwork as being personally symbolic or as depictions of my experiences. However, I do recognize that to some people my art can be viewed as a personal representation. For example, I worked on a small series combining imagery from the Mojave Desert, the place where I was raised, with religious iconography. This series was about the exhaustion often felt from being in a conservative Christian church. I thought of the desert as being viewed as a universal place that is harsh and oppressive, and I compared that environment to a traditional Christian church setting. The individuals who have also experienced life in the Mojave Desert, related with my imagery, however those that hadn't experienced that environment had difficulty connecting with the work. This was the first time I considered that not everyone will understand my artwork. I think about shared experiences and representing the effects of social structures, but I recognize the differences in individual experiences.

I reflect on my past when creating but my artwork isn't a direct response to my own experiences. I strive to evoke empathy, not for myself but for issues affecting so many individuals across the US.

Tamara Murphy: How has being a queer artist played in to developing your vision? Do you think your identity overlaps into your work?

Rae Helms: As I mentioned, I think it is impossible for artists not to think of their experiences and placement within society when creating art. When we talk about art history, we talk in timelines. Artists for centuries have been trying to be avant-garde, new or original, however, by doing so they reject the previous art movement. Historians group artists together, who were directly in conversation with each other, and coin these movements and stylizations years later. I would like to read a quote that talks about identity politics: “The default expectations of the art market and curatorial establishment are aesthetics rooted in white, male, and heteronormative experiences. Identity Politics is therefore an attempt to readdress an imbalance, and to encourage reflection on operations of art history that have systematically disadvantaged those whose artwork did not conform to these expectations.” 1 I understand this as anyone who is not white, male, cisgender, and heteronormative is faulted to be a part of identity politics. In art, this is determined by who the artist represents that is outside traditional normality. Some political artists embrace making work about their personal identity, while others reject the notion of identity politics. I struggle with the concept of identity politics and am somewhere in between the two opposing opinions. My identity is important to my understanding of myself and connecting with other people; however, my queer identity and being raised female has been politicized, while I am so much more than those two defining factors. I also like to roller skate but I am not called a roller-skating artist! My artwork isn't about my identity but a representation of shared experiences resulting from oppressors. Art isn't a place for my pure self-expression or to convey my emotions, but rather a means for self-reflection in a larger social-political and historical context.

Tamara Murphy: Your work covers so many social issues- from gender and sexuality, religion, oppression, homelessness, domestic violence... the list goes on. What inspires you to approach each new work?

Rae Helms: My biggest inspiration comes from my loved ones, other activists and knowing that I am not alone in addressing these issues. I am constantly inspired by the conversations I have with other artists, people outside of art academia, going to protests, and listening to other activists working hard to promote justice. I keep going back to my aquatint Bounty, which was in response to the recent abortion ban placed in Texas and the ten-thousand-dollar bounties the legislation placed on females seeking the right to choose. It wasn't the actual law being passed that inspired me to create this work (that made me depressed), I was inspired when I saw so many other people raising awareness, coming together, and engaging in collective advocacy.

Tamara Murphy: Is it ever too much to carry as one person?

Rae Helms: Sometimes it is overwhelming. Especially since these issues won't be fixed overnight or when I convince myself that I am not doing enough to help. However, having conversations with people in my life that may have not been well versed in the subject, then seeing them reconsider the effects, and showing empathy, is rewarding. I don't think we are free until we are all free, and that thought constantly motivates me to be engaged in advocacy. Working in a print studio and having a print community counters the stress levels I feel about working with political issues. The printmakers I commonly engage with create work about climate change, feminist issues, and racial 1 N/A. “Identity Politics Movement Overview.” The Art Story. Accessed November 1, 2021.

injustices. Engaging in conversations and having support from other printmakers motivates me to continue creating art rooted in activism.

Tamara Murphy: You have many varied uses of the body in your work (softness/vulnerability, sexualized, strong, etc.)- would you define your use of the body as a tool for relatable metaphor or a more direct narrative?

Rae Helms: Right now, I am experimenting with placing the figure back into my work. Instead of representing the figure in a naturalistic way, I am considering how I can further inspire empathy through the use of the figure. One way to do so is by abstracting the figure and representing the body so that the viewer can place themselves into the work. In my recent print, Get Home Safe! (2021), I intentionally used a picture of my brother made into a silhouette. This monoprint was about the anxiety one can feel walking home late at night. The majority of the time, this is an issue affecting fem-bodied people; however, the silhouette in this woodcut is genderless, so more people can place themselves into this experience, even if they themselves haven't felt that anxiety. I examine the body as a political object; I constantly question what gender means to myself and if it is important in my work; the absence of gender is something I am fascinated with exploring. I believe everyone should have conversations about inequalities, despite not directly being affected.

Tamara Murphy: Your sculpture Pull It Together (2020) intrigues me, as someone who works 3- dimensionally. Do you have an interest in exploring more 3-dimensional works in the future?

Rae Helms: Pull It Together is a paper mache sculpture of an androgynous figure who is bound by thread. My sculpture uses sewing materials, metaphorical to feminism. This sculpture represents how often emotions are considered irrational and how common phrases can be harmful. I made Pull It Together in early 2020, right before the COVID-19 lockdown in California. Before the pandemic, I had not fully adjusted to printmaking therefore my work still relied on other craft materials. I was experiencing a lot of confusion during this time, like many others. This was when I redirected my purpose and choice of materials.

Recently, I decided to explore using found objects by removing the rust on the rabbit traps to reveal text. On one trap the text says “The Right to Choose” and the other says “Plan B.” In my art practice, I find more often than not, I am working with what I have access to, constantly discovering new ways to utilize objects and embracing experimentation in the printmaking processes. Thank you for bringing up my sculpture Pull it Together. To be honest, I haven't been acknowledging my older work. I do have an interest in creating more sculptures, but I haven't considered combining the body with future 3-dimensional work.

Tamara Murphy: How did your experience working during COVID-19 affect your work?

Rae Helms: I realized I wasn't as introverted as I had previously believed. I deeply missed being involved in the print studio community and engaging in conversations with other artists. Early in the pandemic, I decided I would spend the rest of my time at university focusing on printmaking. When I started working from home, I embraced experimentation more. I wasn't afraid of messing up in the print studio or harming the expensive equipment. During the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was terrified that I was going to become extremely isolated from the outside world and lose my inspiration for education, however, it became easier for me to communicate with people in my classes online and to speak out more. I gained new friendships that I don't think I would have had if we weren't in this situation. Many people bonded together, despite the difficulties. So many horrible events happened in 2020 and 2021, but I think the urgency for change in our political institutions

became more prevalent than ever before. It is still a challenging time politically; however, I feel as if there has been an energy shift in many communities. People are speaking out and creating more, which is extremely motivating to me.

Tamara Murphy: What kind of impact do you want your work to have on the viewer? With that in mind, who would be your ideal audience?

Rae Helms: I don't have a specific target audience. For the viewers not directly dealing with these oppressions, I strive to inspire empathy and compassion. I hope my work challenges preconceived ideas. On the flip side, for individuals viewing my work that are directly dealing with the injustices that I am representing, I hope they feel heard and supported.

My main goal is to promote conversation. I am content that some of my artwork is not didactic. I hope the juxtaposition of the objects depicted, and sometimes the inclusion of the figure, inspires discussions about social inequality. The title also plays an important role in my work and is another clue to the issues I am talking about. My etching Campus Violence (2021) juxtaposes a bike track with a braid of human hair. The image by itself doesn't immediately look like a political topic, but rather a comparison of the two forms. However, the title in this etching relates the image to the type of violence taking place at universities.

Campus Violence, 2021, Etching, printed size: 9.5x18'

Campus Violence, 2021, Etching, printed size: 9.5x18'

Tamara Murphy: Do you know what is next for you? Short term and on a five-year timeline?

Rae Helms: In May 2022 I will graduate CSU Chico with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Printmaking and a Bachelor of Arts in Art History. This is a huge achievement because I am a first-generation college student. My parents didn't attend college and one did not finish high school. I am also the first of my siblings to attend college. I have been in education all of my life; therefore, graduating is a scary thought. I've always thought that I would immediately go to graduate school, but I've decided to take a year off college. I am excited to see how my art process will change outside of academia. Graduate school is still my long-term goal. However, I can also imagine myself working for a non-profit organization to continue creating art for an issue that I deeply care about. Living in Chico has drastically changed my art practice for the better and going to university here has opened up more opportunities than I had expected. To continue that growth, I believe I need to push myself outside of my comfort zone again by relocating. I've always dreamed of living in a city because I've only lived in small towns. Living closer to a larger city would also allow me to be more engaged in advocacy and I might venture into the realm of public art. The possibilities are exciting to think about.

Footnotes

1: N/A. “Identity Politics Movement Overview.” The Art Story. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/identity-politics/.